My favourite inequalities

Imbalances are ubiquitous in nature. Their very existence is a macrocosm of bizarre phenomena that react in wild and seemingly unpredictable ways. But mathematicians devised a way to reify these imbalances into a formal system that always hold true. Several abstract and difficult problems have been reduced to trivial solutions through a series of logical consequences that arise from inequalities. And much to the irony, we need these inequalities to prove equalities of all kinds.

Over the course of this article, we are going to discuss some of the most important inequalities in mathematics. Please bear in mind that I will not go over their proofs to avoid making this a verbose mathematical discourse! As with all my articles, I plan on keeping this extremely comprehensible and intuitive with a greater on focus on their practicality. But I certainly do not mind expanding on examples to help clear the picture for you.

The Mean Triplet

I consider the Mean-Triplet, more commonly known as the Arithmetic Mean(AM) - Geometric Mean(GM) - Harmonic Mean(HM) inequality, as the father of all inequalites. It is very fundamental and finds tremendous applications in everyday scenarios.

It states that for any non-negative real number, their AM is greater than their GM, which is in turn greater than their HM, with equality only when all values are equal.

Mathematically,

The AM-GM relationship is often used to maximize or minimize functions. The AM is simple and applies equal weight to every value when calculating the mean. The Geometric mean, on the other hand, is used to capture the averaging of compounding effects.

To illustrate this, let us consider the annual returns of an investment for years to be , , and respectively. The formula for the average growth rate for the period is given by

where represents the return for the period and is the total number of periods. We need not really bother ourselves with the intricacies of this equation to understand the Geometric Mean but unfortunately, I love explaining.

The term is called the growth factor. We can arrive at this quite easily when we look at the formula for fractional (or percent) change.

Evidently, the growth factor is simply the ratio of final and initial values, or plus the fractional change. The significance of this lies in the fact that adding accounts for the initial value as well as the growth rate. Here’s an example. Say an investment has grown by (growth rate) in the past year. This means that the fractional increase is times the initial investment. The in includes the original investment. If we multiply with the initial, we get the final return. We can also say that the final value is of the initial value. Similarly, if we incur a negative growth rate (loss) of say , the growth factor would be , meaning the final value is of the original.

Now, multiplying all the growth factors gives us the total growth over all periods combined. And then taking its geometric mean averages the total growth over the entire period. This is important because unlike the AM, the GM successfully accounts for the compounding of each return in successive years. We then subtract 1 from this average to convert it to a percentage. But how did that work? If you noticed, the geometric mean of the total growth is the growth factor. In our previous examples, a growth factor of 1.12 gives us a growth rate and a growth factor of 0.95 gives us a growth rate respectively. This shows that subtracting 1 from the growth factor gives us the percentage increase (or decrease) in our investment. With all of that away, the final average growth rate in our case would be,

Taking the Arithmetic Mean would simply result in

which isn’t quite accurate. Note that the AM is always greater than the GM. The GM is more accurate in averaging rates with data whose relationships are multiplicative or proportional in nature, as in our case.

Additionally, we can also include the Quadratic Mean (QM, also known as the Root Mean Square), which applies a greater weight to the larger values and is often used in averaging varying quantities like AC current and voltage or measuring errors in statistics.

Like the GM, the Harmonic mean is also useful when averaging rates. It is used in finance to calculate analysis metrics like Price-to-Earnings ratio, or in electrical engineering to calculate the equivalent resistance of resistors connected in parallel. Contrary to the Quadratic Mean, which assigns a greater weight to the larger values in the set, the HM punishes the central tendency by applying a greater weight to the lower values. This means that greater the extremes in a series of values, the lower the Harmonic Mean. This is because HM relies on the reciprocals of each value. The smaller the value, the larger is its reciprocal, and consequently, the greater its influence in shifting the mean towards itself. But it obviously cannot be calculated if any of the values is zero, since the reciprocal of zero does not exist.

The simplest example of the Harmonic Mean can be found while averaging speeds. Consider a car moving at km/h for km and km/h for another km. If we take the AM of the speeds, we’d get km/h. But we know that average speed is equal to . If we now calculate the average speed, we get which is equal to the HM of the speeds and not the AM.

Why does this work? It is because the harmonic mean of speeds is weighted by time and not by distance. Speed is inversely related to time. Hence, the time we spend at a particular speed must affect the overall average speed. The slower the speed, the greater is the time spent at that speed and the greater its impact in the average. The AM assumes that each speed is equally weighted, but what matters is not just the speed itself but the time spent at each speed. The HM is correct in applying greater weight to the the lower speeds.

The Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality

The Cauchy-Schwarz is perhaps the most brilliant inequality with far-reaching implications in all of mathematics.

It states that for any two sets of real numbers and , the product of the sum of the squares of each number in both sets, is greater than or equal to the square of the sum of the product of corresponding values of each set.

with the equality holding iff

A corollary definition of this inequality can be found in Vector Calculus, where it provides an upper bound for the for any two vectors and

where and are the norms of the vectors and is the absolute value of their dot product, with equality holding iff the vectors are linearly dependent or one of the vectors is a null vector. A set of vectors are linearly dependent when at least one of the vectors can be written as a linear combination of the other vectors (There exists a scalar which satisfies ).

The inequality provides an upper bound for the absolute value of the dot product of two vectors. Specifically, it states that the absolute value of the dot product cannot exceed the product of the magnitudes of the two vectors. Norm is just a fancy word used to describe the magnitude or length of the vector (in Euclidean space). By expanding the modulus of the inquality, we can determine the range of the dot product.

For the sake of simplicity, I am considering the vectors to be in real space . But the inequality can be generalized and holds true in non-Euclidean vector spaces with complex forms as well. The dot product is just a special case of the inner product in space.

The applications of Cauchy-Schwarz can be seen when we take the cosine of the angle between two vectors

or in the covariance inequality in probability theory

where and are two random variables and are their variance and covariance respectively. It also gives rise to an inequality known as Titu’s Lemma, which is of the form

This is often used as a shortcut for solving inequalities whose numerators are perfect squares.

The Rearrangement Inequality

If you’re familiar with greedy algorithms in computer science, this is exactly what it is.

It states that for any two sets of monotonically increasing real numbers and , the value of , where and denotes the nth value in any random permutation of both the sets, is maximised and minimised when

with equality when the values of one or both sets are equal.

If the above notation looks a little cumbersome, here’s a breakdown of the inequality through an example. Consider three bags of rupee, rupee and rupee notes, each containing notes each. If we are asked to get the maximum amount by picking notes in total, we would obviously pick notes from the rupee bag, from the , and none from the rupee bag. This conclusion is simply common sense. Similarly, if we are asked to get the minimum, we’d pick three rupee and two rupee notes. The rearrangement inequality illustrates this exact “greedy” logic. Any other permutation (or grouping) of the notes, with the given constraint of 5 notes, would result in a value that lies between the two.

This consequently leads us to another famous inequality known as Chebyshev’s inequality.

but when the sequences are oppositely oriented, say

In both the cases, equality is achieved when the sequences are constant. The impact of Chebyshev’s Inequality is widely felt in probability theory. It provides an upper bound on the probability that a random variable (say ) deviates from its mean by more than a definite amount of standard deviations.

where is the mean, is the SD and is the number of SD. This bound is not definitive but only a conservative estimate which works well for most cases, regardless of the type of distribution. Due to this, it is popular in many statistical inferences. Let’s take an example.

The mean () of the subject score for a group of students is and the standard deviation is . If we randomly pick a student, what is the probability that the student has a score which is greater than but less than ?

There are other ways to arrive at the right answer, but we’ll stick to using Chebyshev. Let’s first calculate the (also the z-score), which gives us the number of standard deviations above or below the mean. In this case, . If the values of n were not equal, we would settle with the greater z-score (we are only concerned about the magnitude and not sign). We now need , which is equal to . Therefore

This shows that there is at least a chance that a randomly chosen student has a score between and .

Jensen’s Inequality

This is an extremely powerful inequality (and probably my favourite of all). To understand Jensen’s inequality, let us first explore convex and concave functions.

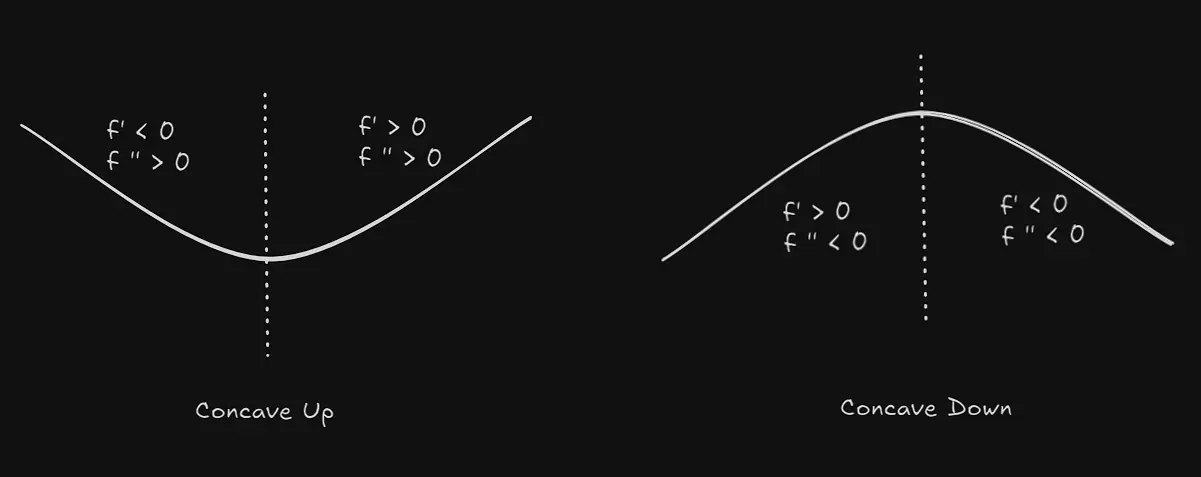

A function is convex (also concave up) if the second derivative, and concave (also concave down) if for all . If , the point is an inflection point where the function’s concavity (or convexity) changes. Further, the sign of the first derivative tells us whether the function is increasing or decreasing in the said interval.

Now, the inequality states that if is convex in the interval , then

and if it is concave, the reverse inequality holds true

The simplest application of this inequality can be demonstrated by proving the AM-GM inequality.

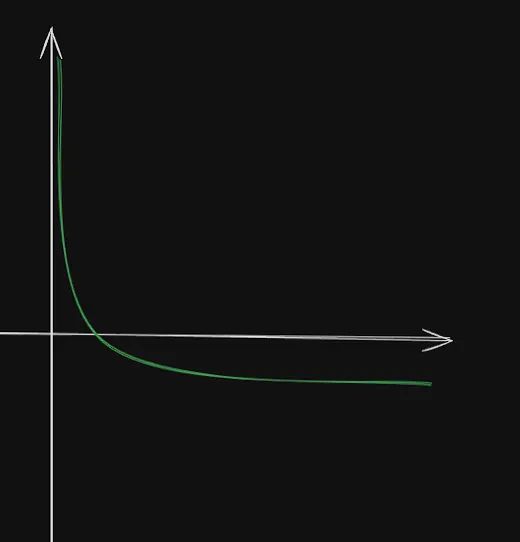

Let us consider a function , whose graph looks like this. It is simply the reflection

of against the x-axis.

The first derivative of this function is , and its second derivative . Since for all , is concave up for . Thus, by using the inequality,

When we multiply both sides of an inequality by , the inequality sign reverses. If you remember the properties of logarithm, you will likely remember these properties.

Our goal is to raise the numerator to a fraction , since we need to obtain the Geometric Mean, which is a surd. If we do this, we have to compensate by raising the power of the base to the same fraction, by following rule 1. Similarly, for the denominator, we know as .

Now, applying the second rule to this inequality, we can replace the fraction with a logarithm whose base is the argument of the denominator ( in this case) and its argument the numerator. Hence, we get

Since the base of the logarithms on both sides are , which is greater than 1, we can remove the function and simply apply the inequality to its arguments.

if , then when and when

This proves the AM-GM inequality. Isn’t it remarkable?

Bonus: The Chicken-McNugget Theorem

This has to be my favourite little theorem of all time, not just for its fancy name, but for good reason. It states that for any two co-prime numbers and , the greatest integer that cannot be written as a linear combination of a and b is . Let’s illustrate this with an example.

Consider a game that awards points and points to a player on the basis of various scenarios. Since, and 11 are co-prime, we can apply the McNugget theorem and find that , which is , is the maximum amount of points that cannot be scored by any player. Thus, scoring points is an impossibility for any player playing the game. After , every point can be represented as a linear combination of and .

You can read the story behind it’s unique name here :)

Conclusion

Mathematics was my top subject throughout school. I probably owe it to my dad, who has a masters in Pure Mathematics, for impressing me early in my childhood. Although I barely participated in any rigorous maths competitions and cannot boast of any prodigious success, my fascination for the discipline has no upper-bounds. You can try the inequalities section in Art of Problem Solving for an in-depth reference or tackle the olympiad problems if you feel up for a challenge.

Always remember to embrace, not suppress the imbalances that wrestle inside you. They all exist for a reason.

Finished in my dorm room (6008), surrounded by a growing scent of rapidly burning candlesticks.